I have in the past ten years tweeted, written and presented about young learners and digital citizenship and coined the term “lived curriculum” to describe the approach I most passionately believe in. Recently it has been suggested that I should unpack this and put a stake in the ground for this term and the pedagogies that surround it. This post is an attempt to place that stake.

I have been involved with the Quest Atlantis program for at least ten years and in that time I have seen tens of thousands of students around the world, some as young as eight years old, grapple with what it means to be part of an online community. More recently my involvement with Massively Minecraft and other Minecraft implementations have reinforced the philosophical stance I cultivated through Quest Atlantis. I want to talk about why that community online experience is so important.

I see many teachers giving students worksheets, watching videos and acting out role plays to assist in students learning what digital citizenship involves. And quite frankly I think it is largely a waste of time. A colleague teaching middle-school reported to me that he had run such a program in his school, for which the students appeared to recognize the major issues, only to that same week engage in outrageous acts of bullying on Facebook. The learning in these programs is too far removed from the context. You have to get into a pool to learn to swim. Yes you can learn some aspects of stroke correction from a video, but actually getting into a pool is assumed necessary to learn to swim. Likewise to teach children to cross a road, we hold their hand and escort them across roads and crossings, pointing out the important things to be observant of as we go. We might watch road safety videos and have fun activities around this but essentially learning to cross a road happening in situ.

Why then do we expect children to understand digital citizenship without being part of online communities? No we do not want to abandon them to all the spaces they could be online or set them sailing into a digital Lord of the Flies. But we want them to engage on their own terms in spaces where they are surrounded by supporting trusted adults. This experiential learning is vital, no worksheet can ever offer the gamut of situations that kids might face online. We are derelict in our duty of care to our students if we do not offer them these experience and seize on the teachable moments as they arise.

In Quest Atlantis teachers are emailed with the transcript of both possibly transgressive AND exemplary behaviors. We do this so that teachers can take up each of those teachable moments and hold dialog, counsel learners and open up these issues. Within the QA online community students are constantly surrounded by trusted adults (other teachers not necessarily their own) who are not their to police the student behavior but as co-learners and support should students seek it. These teachers are asked to model the positive engagement and practices that we want their students to engage in. The same is happening in many very effective school or district-based Minecraft implementations. We certainly saw this in Massively Minecraft.

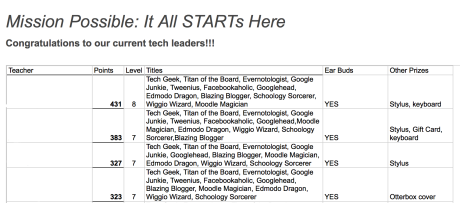

None of the communities that I have engage in have had a set of rigorous do’s and don’ts. What they do have is a community designed charter or a set of positive statements of the behaviors that are supported and admired in this community. Over time in QA, Minecraft and Open Sim we have seen that children quickly become very adept at moderating their own behaviors and community. They readily say “we don’t behave like that in here…” to students acting out. They learn to see how an interaction might be heading is in a negative direction well before it gets there and seize opportunities to support each other in being more positive and a community spirited. Students want to level up to greater and greater responsibility. Who would have thought that the most attractive reward for lots of hard work in the community could be responsibility, leadership and greater accountability. But kids do crave this! They want ownership and opportunities to show they can shine at being good human beings. And every time I have trusted in students to do so they have spectacularly exceeded my expectations. Even more than that they have things they want to say on the matter and such spaces afford their ownership of citizenship issues.

So this is the long winded way of describing the lived curriculum of digital citizenship – an experiential space for students to immerse themselves in the day-to-day interactions of community online. A space replete with opportunities good and sometimes bad. But isn’t it better for kids to trip in this digital space where a someone can pick them up and help them to understand why such a behavior might be considered mean spirited, dangerous or bullying? We can we expect so much more of these learners when they reach the 13 year old acceptance age for much social media if they have been online and experienced the positive value of being together online since they were very young.

Let’s face it, kids are online as soon as they can swipe in an app on an iPad. We need to stop thinking that digital citizenship has an age threshold for introduction or that the digital part allows us to quarantine it. And let’s take to task the separateness of “digital citizenship”. This is about citizenship in all the places it is possible to be lived out. Learning to be a good human being starts when you are born and is the ultimate lived curriculum!